Making the Diagnosis

Aim of this section

This section aims to help doctors, especially doctors in training, to avoid some of the common pitfalls in recognising and treating children with meningococcal disease. It is not a fail-safe diagnostic package: since no symptom is entirely specific to this disease, many children with the symptoms described will not have MD. We hope to prompt doctors to ask "could this be meningococcal disease? when assessing a child in the Emergency Department or on the wards where the diagnosis is in doubt.

back to top^Taking a history

Meningococcal disease is extremely unpredictable. The presentation can be very varied and patients may be difficult to differentiate from those with viral illnesses during the early stages. Most children with MD present as an acutely febrile child and may not have a rash at first.

It is important to take a detailed history and ask parents about the specific symptoms of septicaemia and meningitis. Beware of simply ‘eyeballing’ a child and assuming they have a trivial illness. This is how many mistakes are made. Make sure you have understood what exactly is worrying the parent and why they are seeking help at this point. Be careful if the child has had contact with a case of meningococcal disease even if they have had prophylactic antibiotics as they can still become ill. Ask about travel to sub-Saharan Africa or contact with Hajj pilgrims.15 16

At the initial assessment look for signs and symptoms of septicaemia or meningitis. Some symptoms can be subtle and must be specifically asked about when taking a history.

back to top^Symptoms of septicaemia

- Fever

- Many children become suddenly ill with a fever: the classic picture is of a disease of rapid onset. However, some children develop septicaemia after a simple viral illness. In these cases the symptoms may be initially trivial and last for some time and then suddenly become more serious with a high fever and other symptoms of sepsis.

- A history of a fever in a child presenting afebrile is important.

- Not all children with meningococcal disease (or other serious bacterial infection) have fever17. A fever that subsides after antipyretics cannot be dismissed as viral in origin.

- Hypothermia, especially in infants, may also indicate serious infection 18

- Rigors Children with septicaemia often have rigors19. Occasionally the shaking, if very severe may be mistaken for fitting, but children having rigors will remain conscious.

- Aches They usually experience very bad muscle aches and joint aches making them restless and miserable.

- Limb pain Isolated severe limb pain in the absence of any other physical signs in that limb is a well-established phenomenon in MD20 7. The pain can be very severe and children have been mistakenly put into plaster to treat presumed fractures.

- Gastrointestinal symptoms vomiting, nausea and poor appetite (poor feeding in babies) are common in septicaemia. Abdominal pain and diarrhoea (leading to faecal incontinence in some cases) are less common but well documented21. This can create confusion with gastro intestinal infections.

- Weakness This can become profound.

- Rash Ask about any new rashes or marks on the child’s skin that the parents may have noticed. Note that parents may not realise that the petechiae or purpura or 'bruises' on the child’s skin are a rash as they associate the word ‘rash’ more with a pink ‘measles-like’ rash. They may use other words to describe the rash, for example bruise, spot, freckle, blister, stain or mark on the skin – like chocolate, etc.

- Urine output Ask whether the child has passed urine or had a wet nappy recently. Oliguria is one of the early signs of shock

- Cold hands and feet, mottled skin As septicaemia advances, cold hands and feet and mottled skin are signs of circulatory compromise that parents notice.

- Signs of circulatory compromise - complications of septicaemia

back to top^Symptoms of meningitis

The main symptoms of meningitis are all due to the dysfunction of the central nervous system. Be aware that symptoms can vary according to the age of the child. Symptoms include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Vomiting

- Drowsiness/confusion

- Fits

- Photophobia (less common in young children)

- Neck stiffness (less common in young children)

- Signs of raised intracranial pressure – complications of meningitis

Young children may have fever and vomiting associated with irritability, drowsiness and confusion. They may be very hard to assess and parent’s anxieties about their state of responsiveness and alertness must always be taken seriously. 22

Older children are more likely to have fever, vomiting and complain of headache, stiff neck and photophobia. 7

Teenagers may present with symptoms related to a change in behaviour such as confusion or aggression. These may mimic the symptoms of alcohol or drug intoxication 23.

back to top^Examining the Patient

back to top^The rash

Most patients with meningococcal septicaemia develop a rash 7 24 25 26 - it is one of the clearest and most important signs to recognise. A rapidly evolving petechial or purpuric rash is a marker of very severe disease.

Early stages

In the early stages the rash may be blanching and macular or maculopapular 24 27 (sometimes confused with flea bites), but it nearly always develops into a non-blanching red, purple or brownish petechial rash or purpura.

Macular rash

Maculopapular rash in meningococcal septicaemia

Isolated pin-prick spots may appear where the rash is mainly maculopapular 24, so it is important to search the whole body for small petechiae, especially in a febrile child with no focal cause.

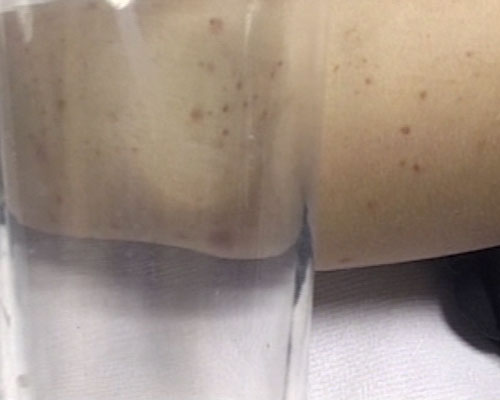

Maculopapular rash with scanty petechiae

Rash in ’meningitis’

In meningitis the rash can be scanty, blanching (macular or maculopapular), atypical or even absent.

Very scanty rash: just 3 petechiae on abdomen (2) and chest (1)*

A few petechiae on mottled skin

Spectrum of meningococcal rashes

Meningococcal rashes can be extremely diverse, and look different on different skin types. The rate of progression can also vary greatly.

Petechial rash*

Mixed petechial/ purpuric rash

Mixed petechial/purpuric rash* on freckled skin

Sparse purpuric rash*

![]()

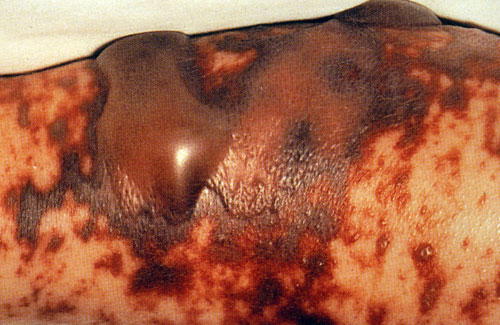

Full-blown purpuric rash of septicaemia

Widespread purpuric rash of septicaemia

Atypical purpuric marks*

Atypical purpuric spots can resemble insect bites

Purple blotches may be larger, resembling bruises*

Purpuric blotches of septicaemic rash can resemble blood blisters

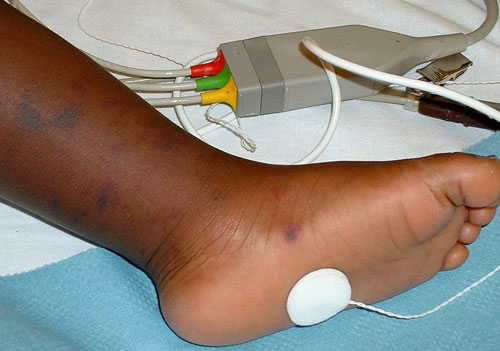

Spotting the rash on dark skin

The rash can be more difficult to see on dark skin,

Meningococcal rash on dark skin*

but may be visible in paler areas, especially the soles of the feet, palms of the hands, abdomen, or on the conjunctivae or palate.

Purpuric rash on dark skin - easier to see on sole of foot*

Petechial rash on conjunctivae

Widespread purpuric rash on dark skin^

Advanced Rash

Purpuric areas that look like bruises can be confused with injury or abuse.

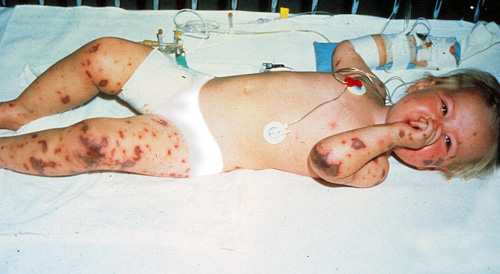

Extensive purpuric areas often over the feet, legs and hands are usually called ‘purpura fulminans’.

Purpura fulminans*

Although some of the causes of petechial rashes are self-limiting conditions, many others, including MD are fulminant or life-threatening, and a non-blanching rash should therefore be treated as an emergency5 19.

It is crucial to remember that the underlying meningitis or septicaemia may be very advanced by the time a rash appears. The rapidly evolving haemorrhagic 'text book' rash may be a very late sign, it may be too late to save the child's life by the time this rash is seen. It is very important to examine children for the signs of meningitis or septicaemia (and raised ICP or shock) and investigate and treat if necessary based on those findings.

back to top^Initial assessment of any febrile child

For all febrile children the following should be undertaken:

- Fully undress and examine systematically. Make a thorough search for a focus of infection: think about the ‘hidden sites’ such as meninges, urinary tract and bloodstream (septicaemia). Mildly pink tympanic membranes or throat do not constitute a focus.

- If a rash is found, it is important to decide whether it is non-blanching. All febrile children with haemorrhagic rashes must be taken very seriously. Although many children with fever and petechiae will have viral illnesses 17 28 29 there is no room for complacency when assessing these children. They must all have their vital signs measured, a decision made as to whether they have signs of meningitis or septicaemia and given intravenous antibiotics. A senior paediatrician should be informed immediately. Some hospitals in the UK may have local protocols on action to take when a haemorrhagic rash if found, depending on whether the rash is petechial or purpuric, and there is work underway to consolidate this48.

- Children without a rash or with a blanching rash can still have MD. The rash may appear later or not at all if the child has pure meningitis and occasionally with septicaemia. Thorough clinical assessment should ascertain whether there are physical signs of serious systemic illness.

- If initial assessment of airway, breathing and circulation reveals that you are dealing with a seriously ill child, ABC should be rectified in line with APLS guidelines30 before proceeding with the detailed examination.

The following clinical signs must be measured and recorded to complete a full assessment:

- Temperature

- Heart rate

- Respiratory rate

- Blood pressure

- Capillary refill time or toe-core temperature gap

Standard technique for measurement of CRT is to press for 5 seconds on a fingertip or toe, or on the centre of the sternum, and count the seconds it takes for colour to return. (Capillary refill shown here on dorsum of foot to facilitate capture on film.)

-

Oxygen saturation measurement (normal value is >95% in air)

- Assessment of conscious level (AVPU)

- Pupil size and reaction

- If rash present record whether it is blanching, extent of rash, speed of development and whether it is petechial or purpuric (Petechial <2mm diameter, purpuric >=2mm diameter). Purpura are highly predictive of meningococcal disease and should be treated as an emergency, with immediate antibiotics and admission. Petechiae alone are less predictive, but must be taken very seriously and especially in combination with other features of septicaemia should provoke urgent action.

Full-blown non-blanching haemorrhagic rash*

Normal values of vital signs

| Age | HR/min | RR/min | Systolic BP |

|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 110-160 | 30-40 | 70-90 |

| 1-2 | 100-150 | 25-35 | 80-95 |

| 2-5 | 95-140 | 25-30 | 80-100 |

| 5-12 | 80-120 | 20-25 | 90-110 |

| Over 12 | 60-100 | 15-20 | 100-120 |

From Advanced Paediatric Life Support—the Practical Approach. 30

back to top^Assessment of a febrile child with suspected meningococcal disease

If MD is suspected, the purpose of the initial assessment should be to identify whether shock or raised intracranial pressure is present and the severity of the illness.

back to top^Clinical signs of septicaemic shock

Septicaemia will lead to shock and multiorgan failure. Shock is a clinical diagnosis. The signs are a result of circulatory failure. The underlying pathophysiology of septicaemia and the capillary leak syndrome leading to these signs are briefly summarised in the pathophysiology section.

A child in early shock may still be alert and have a normal blood pressure.

Child lucid despite advancing septicaemia

The early signs of shock include:

- Tachycardia

- Cool peripheries (CRT>4 seconds) or toe-core temperature gap of >3 degrees

- Pallor, mottling

- Decreased urine output (<1ml/kg/hr)

- Tachypnoea – secondary to acidosis and hypoxia

(In patients with meningococcal disease, signs of shock will usually co-exist with symptoms of septicaemia.)

As shock progresses further signs develop:

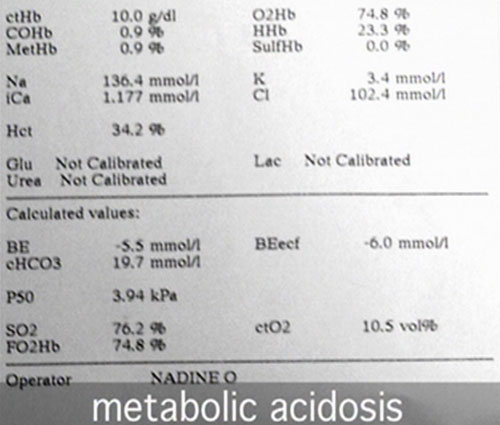

- Metabolic acidosis with base deficit worse than -5

- Hypoxia: PaO2 <10kPa in air or saturation < 95% in air

- Increasing tachypnoea, tachycardia and gallop rhythm

Late signs of shock include:

- Drowsiness or agitation

- Hypotension: in children, blood pressure can be normal until shock is advanced

back to top^Clinical signs of meningitis

When examining a child for signs of meningitis it is crucial to remember that the younger a child the less likely it will be to have neck stiffness or photophobia (especially those <2 years of age). Be guided by the parents as to whether the child is drowsy or behaving inappropriately. Often parents are quick to recognise that the cry of a baby has changed or they are making poor eye contact.

- Babies with meningitis may have a full or bulging fontanelle reflecting the raised intracranial pressure.

- They may feel stiff or have jerky movements or they may be very floppy. Fits are common.

- Drowsiness or decreased conscious level (or fluctuating level) is a very important sign in children of all ages.

- Teenagers with meningitis often present in an aggressive and combative manner rather than becoming drowsy. Drug and alcohol intoxication may be suspected 23.

- Rash: can be present, but more likely to be absent, atypical, scanty or petechial than in septicaemia.

(co-existing with symptoms of meningitis)

back to top^Clinical signs of raised intracranial pressure

Children with meningitis are at risk of developing RICP (see pathophysiology of RICP).

Signs of RICP are:

- Falling or depressed conscious level

- Abnormal posturing; decorticate or decerebrate

- Dilated pupils or unequal pupils

- Focal neurology

- Bradycardia and hypertension

- Abnormal breathing pattern

- Cushing’s triad: slow pulse, raised blood pressure and abnormal breathing pattern – late sign of RICP

- Papilloedema is a late sign, its absence does not mean there cannot be any RICP

Note: Health care workers are encouraged to wear masks when carrying out procedures which may result in exposure to infectious respiratory droplets, for example during resuscitation46.

Patients with RICP may have prolonged capillary refill time and a mild metabolic acidosis. If these signs are present in a patient with a normal heart rate or bradycardia, and a normal or high blood pressure, then they are not due to shock.

The diagnosis of raised intracranial pressure is a clinical one:

- Routine CT scanning is not indicated in patients with meningitis as CT scans are not sensitive in picking up signs of RICP 31 32. It is dangerous to put a child with fluctuating conscious level into the scanner without securing the airway first.

- Lumbar puncture is contraindicated in patients with signs of raised intracranial pressure as ‘coning’ can be precipitated 33 34.

back to top^Lumbar Puncture

Lumbar puncture can be important for treatment if the clinical diagnosis is

in doubt particularly, in children who are febrile without a focus. For children

with obvious meningeal symptoms, microbiological confirmation is valuable for

- duration of treatment

- decisions about prophylaxis and public health management,

- follow up care of children who recover with neurological sequelae, and

- disease surveillance.

However, LP must not be performed when there are contraindications and should

never delay treatment. With modern PCR techniques, CSF samples may still be

positive after antibiotics have killed the organisms.

Check with a senior colleague if you are unsure.

Before attempting lumbar puncture assess HR, RR, BP, CRT, pupils, rash, fundal examination for papilloedema.

Make sure there are no signs of raised intracranial pressure or shock.

- Prolonged or focal seizure

- Focal neurological signs ( including ocular palsies)

- Widespread purpuric rash in ill child

- Glasgow coma score <13

- Pupillary dilatation

- Impaired oculocephalic reflexes

- Abnormal posture

- RICP: inappropriately low pulse, elevated blood pressure and irregular respirations. (indicating impending brain herniation)

- Coagulopathy

- Papilloedema

- Hypertension

Lumbar puncture should also be avoided where there is any cardiovascular or respiratory compromise or if there is local infection at the site of LP.

back to top^Initial laboratory assessment

The tests below should be done on all suspected cases of MD and children who are suspected of having an invasive bacterial infection:

- Glucose

- Full blood count

- Electrolytes and urea

- Calcium and magnesium ( metabolic derangements are common in septicaemia and may contribute to myocardial dysfunction)

- Phosphate

- Clotting studies

- Venous blood gas to measure base excess

- Blood culture

- Throat swab culture

- Meningococcal PCR whole blood (EDTA specimen) to send to reference laboratory

| Parameter | Normal range* |

|---|---|

| Hb | 10.5 to 13.5 g/dL |

| WCC | 5.0 to 15.0 (×109) |

| Platelets | 150 to 450 (×109) |

| Base Excess† | 0 to -3 mmol/L |

| pH | 7.35 to 7.45 |

| HCO3 | 22 to 26 mmol/L |

| PaO2 | 10 to 13.5kPa or 75 to 100mmHg |

| PaCO2 | 4.6 to 6kPa or 34.5 to 45 mmHg |

| Glucose | 3.6-5.2 mmol/L |

| Urea | 2.5 to 6.0 mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 19 to 43 mmol/L |

| Na | 133 to 146 mmol/L |

| K+ | 3.5 to 5.5mmol/l |

| Mg++ | 0.66 to 1.0 mmol/L |

| Total Calcium | 2.17 to 2.44 mmol/L |

| PO4 | 1.60-2.90 mmol/l |

| INR | 1 |

| PT | 9.9 to 12.5 seconds |

| APTT | 26.0 to 38.0 seconds |

| TT | 9.2 to 15.0 seconds |

| Fibrinogen | 1.7 to 4.0 g/L |

*Please note that normal ranges for many variables can differ among hospitals.

†Blood gas reports measurement of base excess (BE), which, when negative indicates that there is a base deficit (acidosis).

back to top^The Glasgow Meningococcal Septicaemia Prognostic Score

The Glasgow Meningococcal Septicaemia Prognostic Score ( GMSPS) is composed of 7 parts, 6 clinical and 1 laboratory value. It is described below.

| Observation | Score |

|---|---|

| BP <75 mmHg age <4 <85 mmHg age  4 4 |

3 |

| Skin / rectal temp difference >3 | 3 |

| Modified coma score <8 or deterioration of 3 points or more in 1hr | 3 |

| Deterioration in 1 hour before scoring | 2 |

| Absence of meningism | 2 |

| Extending purpuric rash or widespread purpura | 1 |

| Base deficit > 8 | 1 |

| Maximum total score | 15 |

The GMSPS was first described in 1987 by Sinclair35. It was devised to assign patients presenting with meningococcal disease to a prognostic category. It is a clinical score that has been validated for use in hospitals when patients first present36. The score was devised to try and identify, at the point of admission to hospital, those patients most likely to have severe meningococcal disease and die. Originally a threshold score above or equal to 8 on admission was associated with a poor outcome. As treatments for meningococcal disease have improved the threshold score has increased.

back to top^Use of the GMSPS

It is useful to score all patients with presumed meningococcal disease when they are admitted to hospital as the score does focus on the clinical features of septicaemia. However, all children with presumed meningococcal disease should have the thorough clinical and laboratory assessment described in this learning tool.

If a child has a low score (<8) on admission to hospital, do not assume

that this child is not at risk of severe disease. It could be that you are assessing

the child early in its disease course. Continue to manage the child according

to the early management protocol described in the learning tool.

It is important that regular repeated thorough clinical assessment is continued

for the first 24-48 hours of the child’s admission – repeated scoring

using GMSPS is a useful way of categorising changes in severity of illness.

back to top^Pitfalls in Diagnosis

Every year children are sent home from hospital with undiagnosed meningococcal disease. This leads to wasted hours in which the disease progresses and children may die unnecessarily. Simple changes to clinical practice may help prevent this. Common pitfalls in practice are explained in this section.

back to top^Contacts of cases of meningococcal disease

After a case of meningococcal disease, there is an increased

risk for school and nursery contacts

People who have been in contact with cases of meningococcal disease are at increased risk of invasive disease. After a single case, close household contacts-usually family-are at the greatest risk, but there is an increased risk for school contacts as well37.

12 year old boy presented with a short history of fever, dizzy and nauseated. A member of his class was then on intensive care with meningitis. His mother was concerned that he might have the same illness.

On examination he was febrile, temp 38.5, alert and orientated.

He was assessed by a doctor who found that he was alert, with no neck stiffness or photophobia. He did not have a rash and his chest was clear. The doctor diagnosed a viral illness and sent him home.

He returned 12 hours later with fulminant septicaemia and died.

Guidelines for the public health management of meningococcal disease are based on the statistical probability of further cases occurring and the risk/benefit balance of control measures that can be taken38. Wider public health action only comes into play after two or more linked cases. Although the great majority of cases of meningococcal disease are sporadic and do not result in further linked cases, clusters of cases do occur. When assessing a child whose classmate has meningococcal disease, consider that this could be the second case that makes the cluster.

Diagnosing "meningitis"

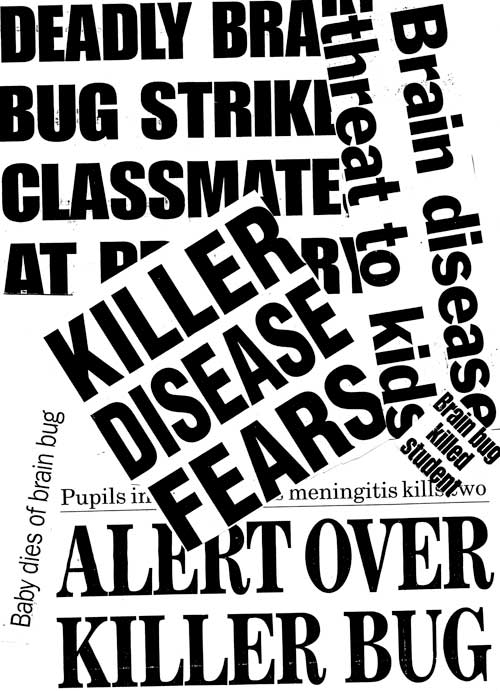

'Deadly brain bug' - the media portray meningococcal disease as meningitis even when the subject is a case of meningococcal septicaemia

Parents are usually not aware that there is a difference between meningitis and septicaemia and it is up to doctors to ask about the symptoms of sepsis and ensure that their clinical examination includes looking for shock.

Making a provisional diagnosis.

A diagnosis based only on symptoms should be viewed as changeable until you have confirmation from investigations.

When giving a child a presumptive diagnosis like 'febrile convulsion' or 'viral illness' remember that it is just that-your best guess.

2 year old admitted with a history of fever, cough, fast breathing and fast pulse noted by the mother.

The child had experienced a 10 minute generalised convulsion at home.

On admission the child had a fever of 39.3, Pulse 220 bpm, RR 35/min, saturations 99 and no rash noted.

A diagnosis of febrile convulsion was made and the child was admitted to the ward.

1 hour after admission the pulse was fast at 186, BP 95/50 and respiratory rate 50. No investigations were sent.

2 hours after admission the child had a second fit for a few minutes. The medical staff decided that this was just a second febrile convulsion and did not change management or investigate. The persistent tachycardia and tachypnoea were not taken into consideration.

During the next 5 hours on the ward there were no recorded vital signs at all. Then the child was noted to have extending purpura and to be shocked. Full resuscitation was started but it was too late and the child died.

How much rash do you need to diagnose meningococcal disease?

A few petechiae on mottled skin Especially in the early stages, or when meningitis predominates, rash may be scanty, blanching or even absent.

Remember that the process of meningitis or septicaemia can be quite advanced before the rash starts to appear, so if you suspect that a child may have meningococcal disease then do not wait for more rash to develop, treat the child immediately.

2 year old boy seen by the GP: acutely unwell with high temp, vomiting, lethargy, unable to keep fluids down. Extra concern - close contact has been diagnosed as having Meningococcal Meningitis

GP examination fever 38.6, pale, no rash, tachycardic but not shocked, irritable on handling.

Seen in hospital: Pale and quiet Temp 39.6, P 155, RR 58 , No rash, thirsty

Given paracetamol, vomited immediately

SHO examination: Very lethargic, sleepy but rousable, Pale

RR 60, P140, No neck stiffness, 2 petechiae in nappy area

Diagnosis ? viral illness

Reviewed by registrar: diagnosis - this was likely to be a viral illness and to admit for observations, to have antibiotics if more rash appeared.

12 hours later- consultant ward round- looking worse with more rash. Investigations initiated.

Hb 10 , WCC 22.5 , Pl 244

pH 7.29 , pCO2 4.39, pO2 4.6, BE -10

INR 2.0 , APTR 1.3

Child deteriorated quickly at this point and died

Other rashes.

If you diagnose a child as having another illness characterised by a rash, make sure that your diagnosis is likely or even possible.

You may be sure of your diagnosis, but if you decide the child is well enough to be sent home, remember to advise parents to return if their child becomes more unwell, even if this is only shortly after being seen.

Teenagers

Approximately 25% of teenagers carry meningococci in the nasopharynx

Teenagers are a vulnerable group. There is a secondary peak in incidence of meningococcal disease amongst young adults aged 15-20 years, with an increased risk of mortality39.

As shown in this learning tool, in the section Development of Symptoms in Meningococcal Disease, signs and symptoms develop later in teenagers than in younger children. Teenagers present to GPs and to hospital later than younger children do, and on average the disease is further advanced in teenagers by the time they get to hospital.

He walked into ED - no rash, alert and orientated. HR 160, RR20, Temp 39, BP80/40, saturations 96% in air.

After 30 minutes he developed rapidly spreading purpura.

Hb 13.7, WCC 1.4, platelets 9.

Na 134, K 3.2, Urea 6.2, creat 163

PH 7.1, pCO2 4.9, pO2 4.1, BE -13.8

He was resuscitated aggressively but died.

Does your diagnosis make sense?

Assessing febrile children and trying to decide what is wrong with them is one of the most difficult tasks in paediatrics

It takes time to take a good history and examine a child properly. Before you discharge the patient from your care make sure that what you have done makes sense and that you can explain your actions and decisions to anyone who may ask.